Why in the News?

- In January 2025 the Supreme Court directed the Union government to draft a comprehensive national law for domestic workers and set up a committee to do so within six months. The present status of that committee’s report is unclear.

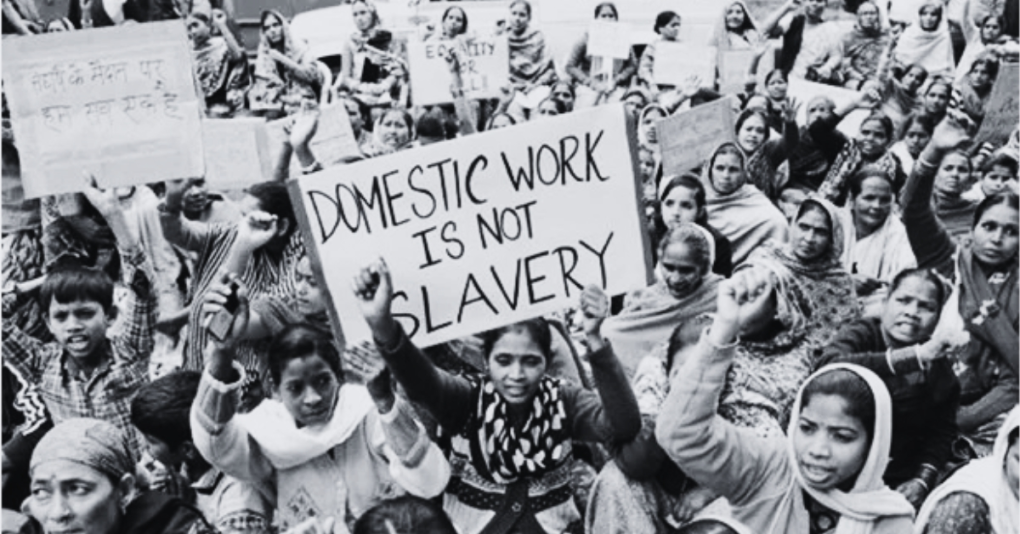

- The Court’s direction came during criminal proceedings about the trafficking and confinement of a female domestic worker, highlighting the urgent need for legal protections for a workforce that is large, mostly female, and highly vulnerable.

Key Highlights

- Scale and vulnerability of domestic work in India

- Estimates vary widely (4 million–90 million), but most domestic workers are women and girls, and many belong to SC/ST

- Work is done inside private homes, which makes oversight, inspection and collective organising difficult.

- Working conditions and common problems

- Domestic workers face harassment, abuse, irregular pay, long hours, lack of contracts, and sometimes child labour.

- Labour supply is mediated by agents or brokers, who often exploit workers.

- Many are migrant (inter-state or international), so state-specific protections leave gaps.

- Existing legal and policy gaps

- India has not ratified ILO Convention No.189 (2011) on domestic workers, though it supported the convention earlier.

- Multiple draft bills and civil-society initiatives (e.g., NPDW’s 2017 draft) exist but no national statute has been enacted.

- Some states have taken steps (Tamil Nadu welfare board; Karnataka Domestic Workers Bill, 2025) but coverage and enforcement are limited.

- Examples of state action and limitations

- Tamil Nadu: welfare board provides pensions, maternity aid and accident relief, but registration is low and minimum wages are often ignored.

- Karnataka (2025 Bill): mandates employer registration, written contracts, minimum wages, overtime and employer contributions to a welfare fund; a model for other states but yet to be implemented nationally.

- Practical policy needs flagged by activists and courts

- Mandatory registration of employers, agencies and workers; issuance of a workbook/record for hours and pay.

- Local complaint mechanisms (panchayat/ULB level) for sexual harassment and labour disputes.

- Structural solutions for housing, portability of social security across states, and regularisation of wages and working hours.

Key Terms

- Domestic Worker

- A person employed to perform household services such as cleaning, cooking, caregiving, gardening, or driving within private homes.

- Employment can be full-time live-in/live-out, part-time, or hourly across multiple households.

- Work is mostly informal, often unregistered, and paid in cash; this complicates labour regulation and taxation.

- High gender dimension: majority are women, exposing them to gendered vulnerabilities (sexual harassment, unpaid care burden).

- Inclusion of domestic workers in labour law is a global trend recommended by ILO standards to ensure equal treatment and social protection.

- ILO Convention No.189 (Domestic Workers Convention, 2011)

- International standard that sets minimum rights and protections for domestic workers: decent work, minimum wages, limits on hours, weekly rest, social security and protection from abuse.

- Ratification requires states to align national laws with convention norms and ensure enforcement mechanisms.

- Convention also recommends registration, regulation of placement agencies, and protection of migrant domestic workers.

- Ratified countries must report to the ILO on implementation and can access technical assistance.

- Minimum Wage (Sector-specific)

- A legally prescribed floor wage for a particular sector or job category.

- For domestic work, minimum wages may be set as hourly or monthly depending on employment pattern.

- Challenges: part-time work, multiple employers and informal payments make enforcement difficult.

- Effective design needs clear wage schedules, payment documentation (workbooks/pay slips), and employer accountability.

- Social Security Portability

- Mechanism that allows workers to retain or transfer their social security benefits (pension, health, provident fund) across jobs, employers and state borders.

- Important for migrant and seasonal domestic workers who cross state lines.

- Portability can be enabled via unique IDs, online contribution records, and centralised funds.

- Reduces vulnerability and creates continuity in benefits even with irregular employment.

Implications

- Human-rights implication: Without statutory protection, domestic workers remain at high risk of abuse, trafficking and exploitation.

- Gender justice: Most domestic workers are women; lack of protections perpetuates gendered economic insecurity and dependency.

- Labour-market formality: Formalising domestic work would broaden social security coverage and improve labour statistics and policy-making.

- Inter-state governance challenge: Migrant domestic labour needs nationally portable rights (wages, benefits, grievance redress) — state laws alone are inadequate.

- Compliance and enforcement costs: Employers, local administrations and inspectorates will need capacity building — but investment yields social protection and reduced exploitation.

Challenges and Way Forward

| Challenge | Way Forward (practical steps) |

| Hidden workplace (homes) — hard to inspect | Use self-reporting workbooks, periodic labour surveys, and empower local labour inspectors with clear protocols for household inspections (with privacy safeguards). |

| Irregular employment & multiple employers | Define employment categories (full-time, part-time, hourly); set hourly minimum wages and rules for aggregation across employers; ensure statutory overtime rules. |

| Migrant and cross-border workers | Make social security portable (Aadhaar/DBT integration); issue identity/work cards; create interstate coordination for enforcement. |

| Weak registration and agency regulation | Mandate compulsory registration of employers, workers and placement agencies; license and monitor agencies; penalise illegal recruitment/fees. |

| Limited grievance redressal | Establish local complaints cells (panchayat/ULB) and district tribunals; fast-track cases of abuse/trafficking; provide legal aid and shelter facilities. |

Conclusion

Domestic work sustains millions of households and the informal economy, yet workers remain largely unprotected. A comprehensive national law — combined with state implementation, mandatory registration, wage rules, social security portability, and easy grievance redress — is essential to prevent abuse, realise gender justice, and bring informal labour within the social security net. State-level initiatives like Tamil Nadu’s board and Karnataka’s draft Bill offer useful models but a national framework is required for uniform protection.

| EnsureIAS Mains Question

Q. “A national law for domestic workers is both a labour and a gender-justice imperative for India.” Examine the key elements such a law must contain and assess implementation challenges at the central and state levels. (250 Words) |

| EnsureIAS Prelims Question

Q. Consider the following statements about domestic workers and legal protection in India: 1. India has ratified ILO Convention No.189 on domestic workers. 2. Some Indian states have enacted welfare measures or draft laws specifically for domestic workers. 3. Compulsory registration of domestic workers and employers is commonly implemented across all States in India. Which of the statements given above are correct? Answer: B. 2 only Statement 1 is Incorrect: India voted in favour of ILO Convention No.189 (2011) but has not ratified it. Ratification would require domestic legal and administrative changes; India still has pending national legislation and relies largely on state-level measures. Statement 2 is Correct: Several states have taken action: Tamil Nadu has a welfare board providing pensions and benefits (with low registration), while Karnataka proposed the Domestic Workers (Social Security and Welfare) Bill, 2025 to regulate contracts, wages and employer contributions. These are partial steps toward protection. Statement 3 is Incorrect: Compulsory registration of domestic workers and employers is not uniformly implemented across India. Where it exists (in draft laws or welfare schemes) coverage is limited; many workers remain unregistered and informal, especially those working part-time across multiple households. |