Why in the News?

- The Finance Ministry recently described the Indian economy as being in a “Goldilocks situation”, marked by moderate growth, low inflation, and favourable monetary conditions.

- This follows a strong 6% GDP growth in Q2 FY2024, peaking interest rates, and stable corporate earnings, prompting analysts to call it a “mini-Goldilocks moment.”

- India exited FY2024 as a $3.6 trillion economy with sustained growth above 7.6%, creating optimism for 2025.

- However, experts caution that this upbeat outlook may mask deeper structural imbalances in the economy.

| Goldilocks Situation 1. Meaning: An economy that is “just right”: neither overheating nor slowing down too much. 2. Growth: Moderate and sustainable GDP growth that supports jobs and incomes. 3. Inflation: Low and stable price rise, keeping purchasing power intact. 4. Policy Setting: Interest rates and fiscal policy balanced to support growth without sparking high inflation. 5. Outcome: Predictable, stable environment that encourages investment and consumer confidence. |

Inflation and Stagnant Wage Growth

- Headline CPI masks underlying stress

- CPI (General) fell from 8% in May 2024 to 2.82% in May 2025, indicating apparent price stability.

- However, this improvement hides the persistent gap between food inflation (CFPI) and general inflation.

- Persistent food inflation volatility

- CFPI consistently remained higher than CPI throughout 2024, peaking at 87% in Oct 2024 vs 6.21% CPI.

- Even during low CPI periods, e.g., Aug 2024 (CPI 3.65%), CFPI was 66%.

- Food inflation disproportionately impacts lower-income groups as food accounts for approximately 50% of their consumption basket.

- Drivers of food inflation

- Unseasonal rains disrupting harvests.

- Supply chain bottlenecks.

- Global commodity price fluctuations.

- Impact on household budgets

- High food prices erode real incomes, forcing compromises in diet quality, essential spending cuts, or increased borrowing.

- Volatility in food prices undermines household budgeting and savings stability.

- Need to focus on core inflation

- Economists like Dr. Pronab Sen suggest targeting core inflation (excluding food and fuel) for a more accurate picture of persistent cost pressures in housing, education, transport, and personal care.

- Wage growth lagging behind inflation

- 2023: 9.2% nominal salary hike → only 5% real wage growth.

- 2020: Real wages fell (-0.4%) despite 4% nominal increase.

- 2025 projection: 8% nominal hike → 4% real wage growth, meaning half the gains eroded by inflation.

- The “silent squeeze” effect

- Stagnant real wage growth reduces household savings and discretionary spending.

- Increases debt reliance, especially in IT product & services, manufacturing, engineering, and consumer industries where hikes are lower.

- The “Goldilocks” narrative is undermined by volatile food prices, persistent cost pressures, and weak real wage growth, revealing a more fragile household economic situation.

| CPI (Consumer Price Index) 1. Definition: Measures the average change in prices paid by consumers for a fixed basket of goods and services over time. 2. Purpose: Tracks inflation from the consumer’s perspective and is used by policymakers (like RBI) to set interest rates. 3. Basket Components: Includes categories like food & beverages, housing, clothing, transport, health, education, etc. Headline CPI vs. Core CPI 1. Headline CPI: The overall CPI inflation, including all items in the basket (food, fuel, housing, etc.). It reflects the total inflation experienced by households. 2. Core CPI: CPI inflation excluding volatile items like food and fuel, to capture persistent price trends. 3. Why Different: Food and fuel prices fluctuate sharply due to weather or global markets; excluding them gives a clearer view of underlying, long-term inflation pressures. CFPI (Consumer Food Price Index) 1. Definition: A sub-index of CPI that tracks only food items in the consumer basket. 2. Importance: Since food is a large share of spending for lower-income households (~50%), CFPI trends directly affect their purchasing power. 3. Volatility: Often more unstable than overall CPI due to seasonal harvests, supply disruptions, and global commodity price swings. |

Income Inequality

- Stagnant real wages as a structural challenge

- ILO and labour economists highlight that without sustained real wage growth, consumption demand, a key growth driver, remains weak.

- This constrains the possibility of a broad-based economic recovery.

- Gini coefficient trends and limitations

- Gini coefficient of taxable income:

- AY13: 0.489 (high inequality)

- AY16: 0.435 (dip)

- Gini coefficient of taxable income:

- AY23 (forecast): 0.402 (further decline)

- Apparent improvement may be misleading as it only captures the formal sector and higher-income taxpayers, ignoring the vast informal economy and wealth distribution patterns.

- K-shaped recovery post-pandemic

- Certain affluent groups and specific industries have thrived.

- Large sections, especially at the lower income levels, have seen stagnant real wages.

- Billionaire count has surged even as earnings stagnate for many.

- Consequences of persistent inequality

- Weakens social cohesion and fosters economic discontent.

- Restricts access to quality education and healthcare for lower-income groups.

- Can undermine long-term inclusive growth despite high GDP figures.

- Reality check for “Goldilocks” narrative

- Robust GDP growth does not equate to shared prosperity.

- When a significant portion of the population feels excluded from economic gains, the idea of a universally beneficial “Goldilocks” economy becomes questionable.

| Gini Coefficient 1. Definition: A statistical measure of income or wealth inequality within a nation. 2. Scale: Ranges from 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (perfect inequality). 3. Interpretation: Higher value means greater inequality. 4. Example: A Gini of 0.35 is more equal than 0.50. K-Shaped Recovery 1. Definition: A post-recession recovery where different sectors or groups recover at uneven rates. 2. Pattern: Some parts of the economy (upper arm of “K”) grow rapidly, while others (lower arm) stagnate or decline. 3. Example: In India post-COVID, formal sector and stock markets boomed, but informal jobs and small businesses lagged. |

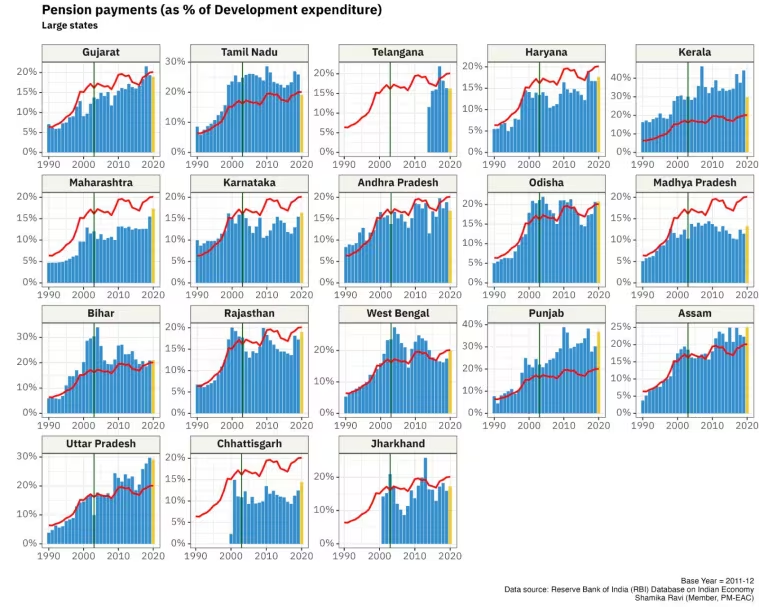

Fiscal Pressures

- Fiscal consolidation trajectory

- Fiscal deficit projected to decline from 4% in 2022-23 to 4.4% in 2025-26 (BE).

- Revenue deficit expected to reduce from 4% to 1.5% in the same period.

- Primary deficit forecast to fall from 3% to 0.8%.

- Concerns despite improvement

- Deficit levels remain substantial even after projected reductions.

- Persistent high deficits require large government borrowing.

- Macroeconomic risks of high deficits

- Crowding out effect: Increased demand for funds by the government may push up interest rates.

- Higher interest rates could deter private investment, slowing business expansion and job creation.

- Public debt burden

- General government debt-to-GDP ratio at ~81% in 2022-23, well above the FRBM target of 60%.

- High debt means a large share of revenues will go towards interest payments.

- Impact on citizens

- Reduced fiscal space for social sector spending (education, healthcare, infrastructure).

- Risk of higher future taxes to manage debt obligations.

- Overall implication

- While fiscal consolidation is underway, high debt and deficit levels could restrict growth potential, crowd out private sector activity, and limit inclusive development.

| Fiscal Deficit 1. Definition: The gap between the government’s total expenditure and its total revenue (excluding borrowings). 2. Formula: Fiscal Deficit = Total Expenditure – (Revenue Receipts + Non-debt Capital Receipts). 3. Significance: Indicates how much the government needs to borrow to meet its spending needs. Revenue Deficit 1. Definition: When the government’s revenue expenditure exceeds revenue receipts. 2. Formula: Revenue Expenditure – Revenue Receipts 3. Implication: Shows that the government is borrowing even to meet day-to-day expenses, not just for investment. Primary Deficit 1. Definition: Primary deficit is the difference between the government’s fiscal deficit and its interest payments on previous borrowings during a financial year. 2. Purpose: Shows the deficit excluding the burden of past debt. 3. Formula: Primary Deficit = Fiscal Deficit – Interest Payments. |

Complicating the “Goldilocks” Narrative

- Multiple structural pressures

- Volatile food inflation continues to erode purchasing power.

- Income disparities persist despite GDP growth.

- Real wages remain stagnant for the majority.

- Limited fiscal space constrains public investment and welfare spending.

- Disconnect between macro indicators and lived reality

- The so-called macroeconomic “sweet spot” is not experienced equally across society.

- Economic gains are disproportionately concentrated among affluent sections.

- Aggregate metrics like GDP growth and headline inflation fail to reflect daily struggles of common households.

- Risks of the “Goldilocks” perception

- Comforting narrative may obscure underlying fragilities.

- Risks masking the urgent need for policy focus on inclusivity and equitable growth.

- True measure of economic strength

- Goes beyond temporary stability in GDP and inflation.

- Requires:

- Sustained growth in real incomes.

- Reduction in inequality.

- Strengthening of fiscal resilience.

- Tangible improvement in quality of life for all citizens.

- Way forward

- Address structural imbalances rather than celebrating short-term balance.

- Prioritise policies fostering inclusive and sustainable prosperity over headline macro numbers.

Implications for the economy

- Household purchasing power and consumption demand

- High and volatile food inflation reduces real incomes for lower-income households and tightens household budgets immediately.

- Lower real wages and precautionary savings reduce discretionary spending, weakening domestic consumption and slowing demand-driven growth.

- Monetary-policy trade-offs and policy effectiveness

- Volatile food prices complicate the RBI’s decision-making: headline CPI may fall while households still feel squeezed, creating a dilemma between containing inflation and supporting growth.

- Relying narrowly on core inflation could underplay the immediate welfare loss suffered by poor households and misalign policy signals.

- Investment, job creation and the quality of growth

- Large deficits and elevated public debt can push up interest rates and crowd out private investment, constraining job-creating capacity.

- Stable corporate earnings at the top do not automatically translate into broader employment gains if investment remains capital-intensive or concentrated in particular sectors.

- Social cohesion, poverty and long-term human capital

- A multi-speed recovery risks widening access gaps in education, health and skills, which erodes long-run productivity and increases social tensions.

- Persistent wage stagnation for large worker segments can increase vulnerability and reliance on debt or informal support networks.

- Fiscal sustainability and limited public goods provision

- Servicing high public debt leaves less fiscal space for essential public investment in health, education and rural infrastructure.

- Limited countercyclical capacity makes it harder to support households during shocks, increasing long-term macroeconomic fragility.

Challenges and Way Forward

| Challenge | Why it matters | Short term Measures (0–12 months) | Medium / Long-term reforms (1–5 years) |

| Volatile, high food inflation | Food is a large share of poor households’ consumption; volatility destroys purchasing power and budgets. | Improve real-time price monitoring and forecasting; expand targeted cash transfers or top-ups for food during spikes; release/target buffer stocks to calm prices. | Invest in cold-chain, storage and rural logistics; reform market regulation (reduce preventable bottlenecks); promote climate-resilient crops and diversification to reduce seasonal shocks. |

| Stagnant real wages and weak labour bargaining power | Low real wages reduce demand and worsen inequality; informality weakens social protection. | Raise statutory minimum wages where feasible; scale short-term wage support for vulnerable sectors; expand employment guarantees in off-crop seasons. | Promote formalisation through simplified compliance and tax incentives; strengthen vocational training and apprenticeship schemes tied to demand; encourage labour-intensive manufacturing investment. |

| Uneven recovery and rising inequality | Concentrated gains weaken social cohesion and constrain inclusive growth. | Scale up targeted social safety nets (PDS, direct transfers) for lagging regions and groups; finance skilling drives in low-income districts. | Reform tax expenditures and broaden tax base to enable progressive revenue mobilization; consider carefully designed wealth or higher-bracket taxes to fund social spending. |

| Tight fiscal space and high public debt | High debt limits countercyclical action and reduces room for public investment. | Reprioritize current spending toward capital and well-targeted social programs; plug obvious leakages and improve GST and income-tax compliance. | Comprehensive tax reform to broaden the base and rationalize exemptions; adopt medium-term fiscal frameworks prioritizing growth-enhancing capex and credible debt targets. |

| Supply- side and structural bottlenecks (agriculture, logistics) | Supply constraints amplify price swings and limit productive capacity. | Fast-track emergency logistics measures in crisis periods (e.g., transport subsidies, temporary market linkages); improve crop-insurance responsiveness. | Invest in rural roads, storage, market infrastructure and digital platforms for better price discovery; implement regulatory reforms to integrate farmers into markets and reduce post-harvest losses. |

Conclusion

The “Goldilocks” label captures a narrow, headline view — moderate headline inflation and strong GDP growth — but it obscures deeper stresses: volatile food prices, eroding real wages, a multi-speed recovery and constrained fiscal space. For growth to be genuinely “just right” for ordinary Indians, policymakers must combine near-term relief (targeted transfers, price-stabilizing actions) with medium-term structural reforms (formalisation, tax reform, rural logistics and public investment). Only a strategy that raises real incomes, stabilises essential prices and rebuilds fiscal headroom will convert favourable macro numbers into broadly felt, durable prosperity.

| Ensure IAS Mains Question Q. The Finance Ministry recently termed India’s economy as being in a “Goldilocks” phase. Critically analyse this claim in light of inflation trends, real wage growth, inequality, and fiscal constraints. Suggest measures to make growth more inclusive and sustainable. (15 marks) |

| Ensure IAS Prelims Question Q. With reference to the recent debate on India’s macroeconomic position being in a “Goldilocks” phase, consider the following statements: 1. The “Goldilocks” economy refers to a situation of high growth, high inflation, and low unemployment. 2. In FY2024–25, India’s headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation declined to below 3%, but food inflation (CFPI) remained consistently lower than CPI. 3. In 2023, India’s average nominal wage growth was higher than real wage growth. Which of the statements given above is/are correct? a) 1 only b) 2 only c) 3 only d) 1, 2 and 3 Answer: c) 3 only Explanation: Statement 1 is incorrect: Goldilocks economy refers to moderate growth, low inflation, and stable conditions, not high inflation. Statement 2 is incorrect: CFPI (food inflation) was often higher than headline CPI (e.g., Oct 2024: CFPI = 10.87%, CPI = 6.21%). Statement 3 is correct: In 2023, nominal wages grew 9.2%, but real wages grew only 2.5% due to inflation. |